| This Tutorial |

Tutorial Viewed: 70795 times

Discussion: Click Here |

Tutorials Home

|

An Astrophotography Primer by strangeghost

Astrophotography is a highly specialized branch of photography that involves

capturing interesting and beautiful images of the night sky. As the title

above indicates, this is not really a tutorial. It is more of a primer,

and introduction to the methods of astrophotography for DPC members. Astrophotos

occasionally appear in challenges or in the forums, and people frequently

say, "How did you do that," "Can I do that with my telescope?"

or similar queries. This is my attempt to answer those questions, and provide

a starting point for aspiring DPC astrophotographers.

Contrary to what you might think, it is possible to create beautiful

images of the night sky without any specialized equipment. In this tutorial,

I will introduce you to four primary types of astrophotography:

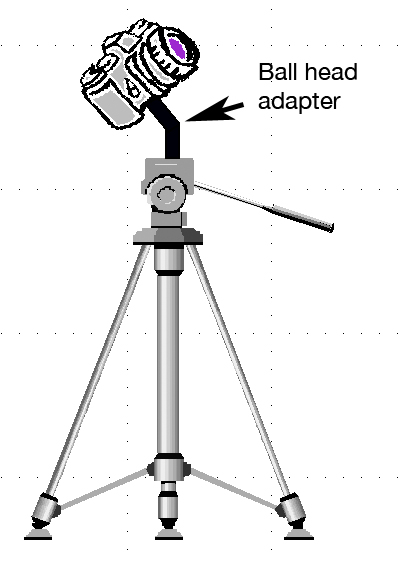

1. Simple fixed tripod shots

2. Piggyback tracked shots

3. Through the scope via prime focus

4. Through the scope via eyepiece projection

These four methods are given in ascending order of difficulty and expense.

Only numbers 3 and 4 require a telescope, though number 2 requires

some type of moving mount to "track" the stars by canceling the

earth's rotation. A telescope is the most common method used to accomplish

this, but there are other ways, as we'll see below.

Before we get started, a word about cameras. While it is certainly possible

to capture astrophotos with conventional point-and-shoot digital cameras,

dSLRs are highly recommended for the following reasons: A) the range of control

they allow over settings, B) their generally superior performance in low light

situations, and C) the availability of high quality lenses to maximize optical

performance.

Now, the four methods

1.

Simple fixed tripod |

|

"24 second tripod shot"

This method is the most popular means of creating beginner astrophotos.

Almost everybody already owns a tripod, but even if you don't, any method

of immobilizing your camera in a secure way while pointing is just fine. I've

taken astrophotos by setting my camera on a picnic table with a coat bunched

up under it to aim at the sky. The shot at right, a 24 second exposure, was

taken with a tripod, using an ISO of 800, I was able to capture a very satisfying

shot of the night sky with the Pleiades and some silhouetted trees. This shot

is straight from the camera with no processing at all other than resizing

for web. By boosting the ISO even higher (and perhaps using a little noise

reduction in post), it's even possible to capture the Milky Way with brief

shots like this. Depending on your focal length, you can expose up to 30 seconds

without the stars starting to trail. The shorter focal length, the wider your

field of view, and thus the longer your exposures can be, but 30 seconds is

a good general rule for how long you can expose a shot without stars trailing.

Fixed tripod method: Cost of additional accessories?

None.

But wait! Don't discount star trails. This is actually one of the

most popular type of astrophotos, and the first method tried by many beginners.

Aim your camera at the starry sky and open the shutter for as long as you

can. Depending on your focal length, stars will start to "trail"

in as little as 30 seconds, as the earth rotates. The longer the exposure,

the longer the trails. By using a smaller aperture (around f/8 or so) and

lower ISO, you can shoot for as long as your batteries will hold out. Note

that any ambient light (streetlights, cars, etc.) will really start to spoil

your image the longer the shutter is open, so darker locations are better.

Also, most cameras will require some type of remote shutter release

or remote control to achieve shutter speeds longer than about 30 seconds.

A star-trail shot with some interesting compositional elements (nice landscape,

interesting foreground objects, etc.) can become a favorite shot very quickly.

"CW Spin 2057 seconds" |

Richard

Hahn's shot is a great example of a star trail. His

34 minute exposure captured the concentric rotation around Polaris and

includes an interesting foreground composition with the mountains. The

longer your exposure, the longer and more satisfying the circular trails

will be. However, with digital cameras, the longer exposures create more

problems with ambient light, sensor noise, and battery limitations. This

is the single shot-style where film cameras (especially old fully mechanical

SLR bodies) still excel - you can literally leave the shutter open for

hours without worrying about anything but dawn.

|

"Stargazer" |

Once you begin to experience some success with the star

trail style, you can try for more static shots, with landscape elements

or interesting foreground compositions. In the tripod-based style, you

must accomplish your shot in about 30 seconds or less to avoid visible

trailing of stars.

Scalvert's

"stargazer" is a great example of creative use of composition

to achieve a very pleasing and interesting astronomy shot. Though he doesn't

give the technical details, it's pretty clear that this was a short (<30

second) exposure after carefully framing up his shot get his telescope

and observer silhouette in place. |

"Sonoran Starlight" |

Kirbic's"Sonoran

Starlight" takes the genre to a whole new level. Note again in his

photographer's comments his use of the 30 second exposure (the "sweet

spot" for such non-tracked images) to obtain this gem. Fritz shot

this on a night with a bright moon, which is how the landscape was so

pleasingly illuminated. You can also see the bright glow of the moon just

off the upper right corner of the photo. |

"Exit the solar system. Comet McNaught. To return in 300,000 years"

|

I include John

White's photo of Comet McNaught here because it is simply one of the

finest examples of opportunity, skill, and execution you'll ever find.

Note again his use of the sweet-spot 30 second exposure. |

"The Mortal Moon" |

And finally, my own "Mortal Moon" shows what

can be done with the fixed tripod method and a whole bunch of exposures

assembled in Photoshop to create a true "time lapse" image,

in this case, of a lunar eclipse in progress. Though it looks quite sophisticated,

it's really just a camera on a tripod with an image shot every four minutes.

Quite a lot of planning and post-processing went into the creation of

this shot. Read the photographer's comment for the whole story. |

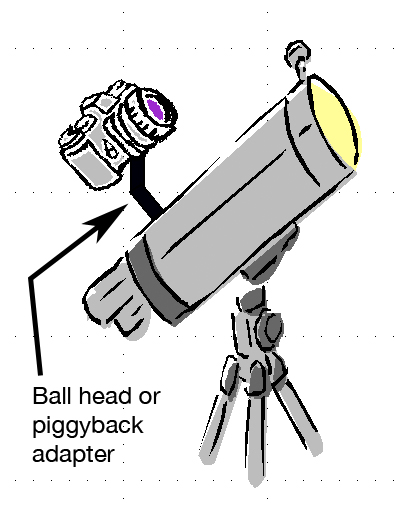

2.

Piggyback tracked shots |

|

"Piggyback illustrated"

"Piggyback Camera"

The term "piggyback" refers to the fact that your camera

is now mounted on top of something - usually a tracking telescope - to achieve

the task of tracking the moving sky (or canceling the Earth's rotation). This

allows you to achieve sharp, longer exposure shots of the sky without the

stars being allowed to trail at all. Most people solve the tracking problem

by piggybacking their cameras on telescopes equipped with sidereal

drives. However, it is possible to build a device to do this without a telescope

(see this Wikipedia article on Barn

Door Mounts). Barn Door Mounts can be built for as little as $20-$30 in

materials and a little work-shop ingenuity. In the heyday of astronomical

do-it-yourselfness, nearly every aspiring astrophotographer had one of these.

They are much less common now, but do a Google search on those terms, and

you'll find loads of examples, with budgets and instructions (lazy? here,

I'll do it for

you).

I own a telescope with a sidereal drive so I use the telescope

piggyback method when I do this type of photography. (see this

pic of my scope with piggyback mount and ball-head attached and ready

for a camera.)

Piggyback method: Cost of accessories? $100

to several thousand.

The first picture at right shows my friend's medium format film

camera mounted piggyback on my telescope ready for an evening of Astrophotography.

The second shot is three views of my Canon 10D mounted piggyback on a 12"

telescope. Note again that the camera and lens are on top of the

telescope (e.g., piggybacked) and not looking through the telescope.

This is where most people misunderstand this method. The camera is using the

telescope only to hitch a ride and make use of its ability to move; it is

not making any use of the telescope's optics whatsoever.

Whether using a barn-door mount or a tracking telescope, it is

vital that the mount be properly polar

aligned (Wikipedia link) to achieve accurate tracking of the sky. When

accurately polar aligned, your camera will stay pointed at your celestial

target as the Earth rotates beneath you.

"Summer Milky Way" |

As with the fixed tripod method, the piggyback method

can be generally split into two methods: First, the wide-field shot. Using

a lens of very short focal-length, you can capture huge expanses of the

night sky - entire constellations or more. My favorite target in the wide-field

category is the Milky Way itself, our home galaxy. Seen with the naked

eye from a very dark site, the Milky Way is a faint, hazy band of light

that seems to span the sky. Seen with the long-exposure eye of a piggybacked

camera, it is simply beyond belief.

This shot, with a 12mm wide-field lens, captures the beauty of the summer

Milky Way as seen from a very dark location in northern Wisconsin. Note

the sheer number of stars visible in this shot. This was a four-minute

exposure. |

"North American Nebula" |

In the center of the above image you'll recall seeing

a faint reddish nebula - the North American Nebula. This shot, taken with

a 50mm lens, zooms in a bit on that same region. This nicely illustrates

how you can achieve different fields of view - or different levels of

magnification - by changing lenses on your dSLR. This was a three-minute

exposure. |

"The Andromeda Galaxy" |

By using longer and longer focal length lenses, you can

achieve significant magnification and some stunning and nearly unbelievable

shots. This shot of the Andromeda Galaxy was done using my 400mm

prime, mounted on my camera, with my camera mounted piggyback on a

tracking telescope. Most people, on seeing an image like this, assume

that it must have been taken with a powerful telescope. Not at all. A

good, sharp lens and a properly aligned tracking mount is all that is

required.

I don't intend to make this sound simple. By upping the focal-length

of the lens, the difficulty level of this type of photography increases

exponentially. Any errors in polar alignment are magnified (stars will

trail in long exposures if the polar alignment is not very close to perfect)

and achieving perfect focus can be a source of extreme frustration. However,

the rewards are significant, as illustrated by my final example. |

"M42 (Orion Nebula)" |

I consider this shot one of my crowning achievements in

astrophotography. Again, shot with the 400mm lens, this shot of the Orion

Nebula was a combination of several shots of varying exposures (from 60

seconds up to three minutes) to achieve proper exposures over the size

of the nebula (it's relatively bright at the center and dimmer around

the edges). Since Orion is a winter constellation (in the northern hemisphere),

this shot also required braving brutally cold temperatures for several

hours to finish the job. |

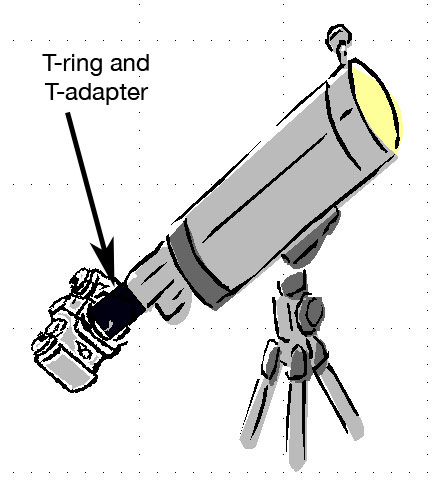

3. Through

the scope via

prime focus

|

|

Prime focus method: Cost of additional

accessories? $1000 and up.Prime focus astrophotography

is what most novices think of when they think of sky shots. I include it here

mostly for completeness' sake. It is listed third because this type astro-shooting

is where difficulty and cost of necessary equipment are truly maximized. I

simply cannot state this strongly enough: prime focus astrophotography

is hard. And expensive. Did I mention that it is hard? OK, I think

my point is made.

The expense of this method comes primarily because prime focus

requires the use of a telescope. And not just any telescope, but a good, well

built, optically excellent telescope. Cheap department store scopes like the

ones you'll find in Sears or Walmart will simply not work. I'm not going to

make this tutorial a lecture on what telescope to buy, but basically you need

a suitable telescope and a very heavy, very stable mount (what is essentially

a tripod for telescopes). These mounts must be sturdy enough to carry the

weight of the telescope and camera gear, must be equipped with a drive to

track the stars, and must be very resistant to vibration and wobble. It is

not unusual for a serious amateur astronomer to spend a thousand dollars or

more on a good mount, and that much or more for the telescope. We're starting

to talk serious money now.

"Camera ready for prime focus"

"Prime focus accessories"

Prime focus astrophotography requires an SLR because to do it,

you must remove your SLR's lens and attaching the camera directly to the telescope,

effectively using your telescope as the lens. All that's required to do this

is a ring adapter designed to fit your camera's mount (Canon, Nikon, etc.)

and a "T-Adapter" which includes an eyepiece barrel that slides

into your telescope's eyepiece opening. Having achieved this setup, aim your

telescope, set the exposure, and fire away. My telescope is a 2000mm focal

length Celestron C8. When configured like this, it effectively becomes a 2000mm

long lens!

"Prime focus moon" |

The moon, shot with my 30D mounted at prime focus on my

Celestron C8. Note the slightly soft focus. I include my own pathetic

image here only to highlight the skill of the two photographers whose

work appears below. This type of astrophotography is hard (have I mentioned

that?), and as a result, this is my least practiced and least utilized

method. If I want to shoot the moon, I can achieve better results with

other methods (see eyepiece projection below). True prime focus astrophotography

is a deep well of time, money, and sweat. Those who practice this method

are the most dedicated of souls and they have earned my full respect.

See the next two pictures. |

"The Andromeda Galaxy" |

John

Lanoue's photo of the Andromeda galaxy is a superb example of long-exposure

photography with the camera at the telescope's prime focus. Taking a shot

like this requires that the tracking of the telescope be guided for razor-sharp

precision. Without going into too much detail for this tutorial, that

involves using a secondary scope to watch a star on the cross hairs of

an eyepiece, and use a hand-controller to manually keep the scope directly

on target for the duration of the exposure (or multiple exposures). See

next example. |

"M8, M20 - Lagoon and Trifid nebulae in Sagittarius" |

This image, by Paschalis

Bartzoudis, is another stunning example of deep sky photography via

prime focus. I just can't emphasize enough how skilled these guys are,

and how much patience, dedication, and dollars this approach to astrophotography

takes. My hat is off guys. Thanks for letting me use your pics in this

tutorial. |

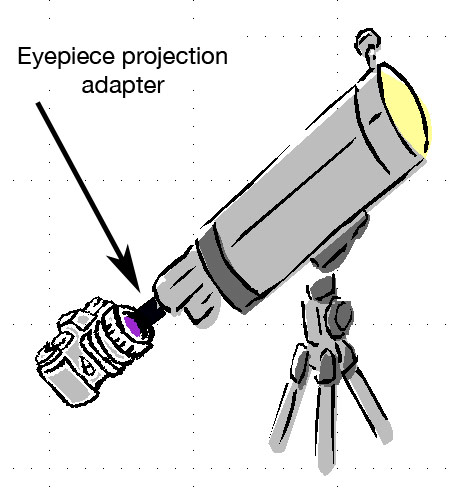

4. Through

the scope via

eyepiece projection

|

|

"eyepiece projection assembly"

"eyepiece projection accessories"

The final method is similar to prime focus in that the camera is

actually looking through the telescope, but this time, you leave the eyepiece

on the telescope, and the camera looks through the eyepiece. The setup is

pictured at right shows my Nikon Coolpix 4500 camera and the necessary adapters

to attach the camera to the eyepiece. There are as many ways to do this as

their are cameras to do it with. The adapter shown here has three thumbscrews

allowing you to clamp it to the barrel of the eyepiece. The other side has

threads that match the lens assembly of the Coolpix 4500. Any eyepiece inserted

in this way will be held snugly in front of the camera's lens, allowing the

camera to see - and photograph - what the eye would normally look at through

the eyepiece. As with the prime focus method, this method is very hard to

master, but very rewarding. This method is most useful for obtaining images

of bright objects like the sun, moon and planets. Many birders also use this

method with spotting scopes, and call it digiscoping.

"Crescent Moon - eyepiece adaptor" |

A shot of the moon using the eyepiece projection setup.

This is the method I use most often when shooting through-the-scope.

I can achieve wonderful shots of the moon, the sun, and other

solar system objects. Because my targets for this type of shooting are

bright objects like planets, the sun and moon, they don't require long

exposures and are thus not as difficult as shooting faint objects like

nebulae, galaxies and star clusters. For those objects, I prefer method

#2 as discussed above. |

"Jupiter" |

An example of my planetary efforts. Again, shot with

the Nikon 4500 through eyepiece/scope, this type of astrophotography

adds yet another layer, that of multiple image post-processing. As

I've written elsewhere, this method utilizes dozens, hundreds, or

even thousands of separate exposures of your target, which are then

stacked or combined using specialized software, to achieve stunningly

sharp and detailed images of the moon, planets or other objects. Shooting

the planets in this method is again, one of the hardest to master methods

of astrophotography. |

"Mars" |

Another of my planet shots, this time Mars during its

close opposition of 2003. This type of astrophotography allows you to

capture more detail than can been seen with the naked eye by virtue

of stacking and averaging multiple images in post processing. |

"The Sun" |

Same type of capture, but this time the sun, with the

aid of a proper solar filter. |

Astrophotography

and DPC

As a rule, astrophotos do not do especially well in DPC challenges,

unless they're spectacularly well done with considerable artistic "wow"

factor. The average DPC voter is not going to recognize how hard you worked

to obtain a fuzzy image of a galaxy, and shots of the moon are a dime a dozen.

To get the voters' attention with an astro shot, as with any challenge, you

need to hit them upside the head with a drop-dead gorgeous shot. That means

thoughtful and artistic composition, emotional impact, and nailing the technicals

(sharpness, color, etc.). Below are a few examples of some DPC shots (both

challenge and non-challenge) that I have been extremely impressed with over

the years, and that have been received well by other members too. All images

are credited to the original photographers unless they're by me.

"the Moon and Me" |

A blue ribbon for Mark

Peters in the Negative Space III challenge, and why not?

Simply stunning. Note the use of the 30-second sweet spot again. |

"Exit the solar system. Comet McNaught. To return in 300,000 years."

|

I've already referred to John

White's outstanding comet shot above, but I just have to come back

to it here. This one earned him a blue in the Exit challenge,

and it's not hard to understand why. This photo has everything: a stunning

subject well placed, excellent landscape and foreground objects of interest,

deeply saturated colors; it's just a feast for the eye in every regard.

If a this comet is only going to return every 300,000 years, you've got

to take advantage of it, and John sure did! |

"Starry, Starry Night in the Italian Alps" |

I can't resist including Jeffrey

Levy's outstanding Alps shot here. Not only did it place very respectably

in a Free Study, it was also taken with a point and shoot camera!

Simply an outstanding result from the hand of an excellent photographer

with modest equipment. |

"Absolute Still" |

Skip

Rowland's"Absolute Still" earned him a blue, but more than

that, as of this writing, it's the 7th highest rated image in DPC history.

That's saying something. Look up "great picture" in the dictionary

and this photo will appear beside whatever definition there is. Scary

good. |

"Madison Moonrise" |

I include this one of mine, not only because I am totally

ego-involved in this subject, but because I have also gotten some pretty

good feedback on this shot. It's part of a series I've been working on

for years to get the definitive moonrise shot over the Madison skyline.

|

"And dusk becomes night..." |

And another one of mine. I have to say, on this one I

was robbed! 5.79 in a basic editing challenge? What were the voters thinking??

<grumble, grumble>

The thing about the six shots listed here? They were all shot

using method #1, a camera and a tripod. No fancy equipment, no piggybacking

on a telescope, no nothing. Just good photographers with good imagination

and execution. This stuff ain't rocket science folks. Get out there and

shoot the sky! |

DPC's various rulesets create some interesting opportunities for

astrophotographers. Basic Editing is, of course, limited to a single exposure.

However, the new revision of Advanced (December 2007) now allows for up to

10 exposures of the same scene to be integrated in post-processing, opening

the door for many traditional astrophotography post-processing tricks to be

used legally for challenges. The Expert Editing (trial) rules have always

been "astro friendly," allowing extensive post-processing modifications

and the inclusion of potentially as many exposures to created stacked composites

- a common astrophotographer's trick.

So what are you waiting for? Get your tripod and remote shutter

release and get out there and shoot some stars!

Home -

Challenges -

Community -

League -

Photos -

Cameras -

Lenses -

Learn -

Help -

Terms of Use -

Privacy -

Top ^

DPChallenge, and website content and design, Copyright © 2001-2025 Challenging Technologies, LLC.

All digital photo copyrights belong to the photographers and may not be used without permission.

Current Server Time: 12/17/2025 01:33:23 AM EST.

|